San Francisco’s Coit Tower, a jewel in the legacy of art-deco architecture and social-realist art, turned 85 this week.

The landmark has graced one of San Francisco’s tallest hills (Telegraph Hill) as a testament to art, architecture and design and is one of the most iconic images associated with the city, towering over the Bay and visible from many points around the Bay Area.

The landmark has graced one of San Francisco’s tallest hills (Telegraph Hill) as a testament to art, architecture and design and is one of the most iconic images associated with the city, towering over the Bay and visible from many points around the Bay Area.

In the current highly-divided, hyper-partisan era where once again, right-wing populist and authoritarian movements, imbued with nationalist and nativist sentiment proliferate across many global urban environments, it is worth looking back to the 1930s in a moment of reflection.

Originally opened in 1933 as a monument to those who died in San Francisco’s earthquakes and fires, the tower’s lobby was painted by 27 artists commissioned as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘Public Works of Art’ project, an early New Deal Program (which would morph into the larger Works Progress Administration, from 1935-1943).

Most of the artists were students and faculty at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA), and the murals are peppered with left wing political motifs and symbols.

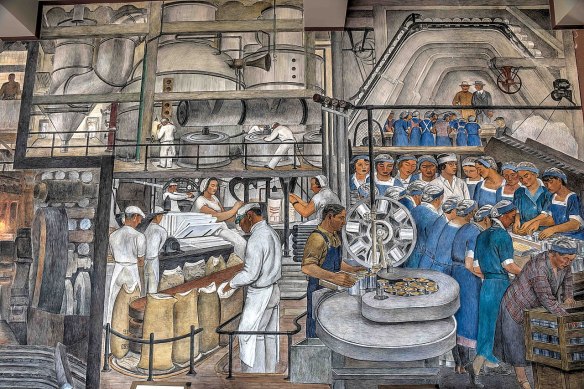

Maxine Albro’s mural of California Agriculture and Ralph Stackpole’s ‘Industry of California’ mural depict both the industrial and agricultural dynamism of the state but also hardship and pain, in the style of social realism that was a popular outlet for Marxist artists in the 1930s.

(Above – Maxine Albro’s ‘Agriculture of California’)

(Above – Maxine Albro’s ‘Agriculture of California’)

(Below – Ralph Stackpole’s ‘Industry of California’)

A visit to the Coit Tower, therefore, is both an aesthetic and political experience, immersing the visitor into the ‘structure of feeling’ (to borrow from Raymond Williams, 1977) of the mid 1930s against the backdrop of present-day San Francisco. This is a study in contrasts. San Francisco, wealthy then, but now the golden and somewhat dystopian center of the global technology industry, beckons from the tower’s windows. The murals, however, produce an affect of simultaneous darkness and optimism, and one steps into the uncertainty, dread, hope and electric energy of the 1930s when entering the tower’s lobby.

A visit to the Coit Tower, therefore, is both an aesthetic and political experience, immersing the visitor into the ‘structure of feeling’ (to borrow from Raymond Williams, 1977) of the mid 1930s against the backdrop of present-day San Francisco. This is a study in contrasts. San Francisco, wealthy then, but now the golden and somewhat dystopian center of the global technology industry, beckons from the tower’s windows. The murals, however, produce an affect of simultaneous darkness and optimism, and one steps into the uncertainty, dread, hope and electric energy of the 1930s when entering the tower’s lobby.

Of all of San Francisco’s towers, from the Ziggurat-like new Salesforce Tower (the city’s tallest) to the abstract and mid-century Transamerica Pyramid, the Coit Tower arguably has and will age the best. There is a timeless quality to it. It stands as a beacon to the possibility of urban beauty at the nexus of philanthropy, state spending, politics and art. There is nothing banal about it, nor is it vulgar or out of scale. The political questions raised, and arguments made, are as prescient now as was the case in depression-era 1933, with the world facing the rise of dangerous nationalist despots and revolutionary movements.

The Coit Tower also stands as a sort of left-coast mirror to another ‘Tower’ on the East Coast, perhaps the modern equivalent: the 1980s, reflective glass, golden monument that is Trump Tower. If the Coit Tower is an emblem of urbanism in 1930s America, then perhaps Trump tower is emblematic of cities today. But the Coit Tower is more than just an architectural relic: it is a blueprint for a possible return to, or even a new golden age of government-commissioned art in the public realm. At a time of renewed radical politics and hope mixed with despair, a new Coit Tower is needed as an urban, political, and cultural beacon.