40 years ago (in 1978), the first of Armistead Maupin’s ‘Tales of the City’ installments appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The ‘Tales’ would eventually be published as 9 novels, from the first ‘Tales of the City’ to 2014’s ‘The Days of Anna Madrigal’. Maupin, who came of age as a young gay man in San Francisco during the halcyon pre-Aids golden age of the 1970s, chronicled a changing city through vignettes surrounding a cast of memorable characters. These characters are archetypes of the San Francisco of-then, and according to Maupin, all bits and pieces of the author’s personality, a sort of dramatized autobiographical sketch. Maupin, hailing from a conservative North Carolina dynasty, found liberation in San Francisco. But alongside liberation, much quirkiness, whimsy, satire, and yes, darkness.

What is most remarkable about the ‘Tales’ series is the way it captures the essence of a vanished world. San Francisco at the turn of the 1980s, just before AIDS decimated gay life in the city and forever transformed the relationship of gay men to urban space. But also, before San Francisco’s first tech boom (which ramped up in the mid-late 1980s) and began the violent cycles of gentrification that continue today in ‘web 2.0’. San Francisco before the murder of Harvey Milk, Mayor Moscone and the mass-suicide of the ‘Jonestown’ cult, (which all happened in November 1978). San Francisco before the neoliberal and growth-friendly leadership embraced whole-heartedly the Manhattanization of downtown and oversaw the replacement of the South-of-Market district from a working-class, artist and LGBT enclave to the dot.com playground it is today. The San Francisco captured in ‘Tales’ is weird and rough around the edges, yet endearing.

In Maupin’s ‘Tales’, sexuality is non-binary and interwoven, with several characters (straight, gay, bisexual) enmeshed in various liaisons. In ‘Tales’, San Francisco is inexpensive and smart phones are non-existent. Dates happen at the roller skating rink or the bath house. There are no Apple Watches or Alexas.

The earnest young gay man, spreading his social (and sexual) wings for the first time, encapsulated in Michael Tolliver or ‘Mouse’. The naïve and white-bread Midwest newcomer, opening up to West coast libertinism and hedonism, in the form of the young woman, Mary Ann Singleton. The mysterious, elegant and avuncular Anna Madrigal, landlady with a secret (and a ready bowl of pre-rolled joints), ultimately one of the most memorable and perhaps earliest significant transgender characters in popular culture. The carefree and bohemian (and bisexual) Mona Ramsey, who takes Mary Ann under her wing.

And a supporting cast of San Francisco types: the WASPY socialite DeDe Halcyon (of Pacific Heights) and her scheming, bisexual husband Beauchamp Day. The lothario Brian Hawkins. The rough-as-tumbleweed Momma ‘Mucca (from Winnemucca), who runs a Nevada desert brothel but has complex ties to the urban characters.

This San Francisco is quaint and small-town, and yet, one can still find these stereotypes around the city, recycled for new generations. Despite the city’s changes, encroaching mono-culture and sanitized urban spaces, it retains a powerful gravitational pull for the adventurous, the queer, the questioning, the naïve, the young.

‘Tales’ was made into a successful TV miniseries in the early 1990s (starring Olympia Dukakis as Anna Madrigal and Laura Linney as Mary Ann Singleton) and is now being again made into a series (with Linney attached to the project) updated for the millennial age, produced by Netflix.

Characters ‘Mouse’, ‘Mary Ann’ and ‘Mona’ in the TV Series ‘Tales of the City’ (Channel 4 UK, PBS/ Showtime US)

If there is a critique of what ‘Tales’ captures / captured, it would be in the things absent. Maupin had a deep window into white, WASPY and gay San Francisco and dissects that personality spot-on, but there are few to no characters of color and San Francisco’s Asian and Latinx cultures are seen as supplementary appendages and not as the central motifs that they are (alongside Gay culture, WASPY old Pacific Heights, the Hillsborough set, etc.) But Maupin’s world did not extend to the city’s edges nor are ‘Tales’ meant to be a sociological analysis of class, race and ethnicity in the Bay Area. Rather, they are snapshots of a certain time, a certain place, and a certain magic in a city that at least historically has been a place of awakening, self-knowledge, and above all, love and freedom.

The geographic center of the series is ‘Barbary Lane’, the garden-filled mews high on a steep hill, often shrouded in fog, within ear-range of the ubiquitous fog horn, where Mary Ann Singleton, Anna Madrigal, and several other characters live. Barbary Lane was based on the real ‘Macondray Lane’, located in Russian Hill.

Macondray Lane in Russian Hill, stand in for ‘Barbary Lane’ in ‘Tales of the City’

This collection of characters living together on such a picturesque mews is, too, a relic of history: it is highly unlikely today that such a quirky assemblage of bohemians would be able to afford Russian Hill, let alone anywhere in the city. Mary Ann Singleton after all came to San Francisco from Cleveland without a job! (But quickly found one, thanks to the kind patriarch and advertising executive Edgar Halcyon, father of DeDe Halcyon, but then, I digress into spoilers..).

So, looking back 40 years, and with ‘Tales’ about to be re-released by Netflix, I have mused on what a ‘new’ episode might be like, given today’s San Francisco. I will close with a bit of mock dialogue-cum-fan fiction, of what a synopsis of the episode ‘November Smoke’ might contain.

II. Fictional Episode of ‘Tales of the City’: 40 Years on – ‘November Smoke'” (Courtesy of Jason Luger).

Scene: November 11, 2018. The air in San Francisco is thick with smoke and ash particles from record breaking wildfires hundreds of miles away.

Mary Ann Singleton, from Cleveland, arrives in the city with hopes and dreams and some training with Microsoft Office Suite. She is ‘ok’ with Excel, in her words.

Mary Ann has heard about an apartment open house in Russian Hill. The apartment is 400 square feet with a shared bathroom with two other units, but it looks cute in the photos. Mary Ann saw that the price said “$4,500 per month” but assumed it was a mistake – surely it was $450 a month, still more than such a unit would cost back home in Cleveland. She walks up a steep hill and almost doubles-over in a coughing fit – the air is hard to breathe. The smoke is so thick that Mary Ann doesn’t notice the Coit Tower, which would be visible straight ahead on a clear-air day. Mary Ann stops half-way up the hill to take a rest, and notices a woman sitting on the curb to her right. The woman does not appear to be wearing pants, and is furiously scratching herself, and Mary Ann notices there are open sores covering the woman’s legs. ‘My goodness’, Mary Ann catches herself saying aloud.

Upon arriving at the address she has written down on a piece of paper in her pocket, Mary Ann knocks on the door of the apartment, and a friendly man opens it. Mary Ann sees that there are 20 people already inside, taking pictures. All white (like her), but much younger – they seem to be in their early 20s (Mary Ann is almost 30). Mary Ann sees several of the others hand packages to the man (who must be the landlord) – credit histories? Bank statements? Employment references? Mary Ann has none of those things. Dejected, she leaves.

Luckily, Mary Ann has a friend she can stay with – a gay man named Michael. Mary Ann meets up with him, and they head to lunch in a trendy neighborhood (having looked at the menu, Mary Ann isn’t sure how she’ll pay for her meal – but hey, she has just arrived, should treat herself). Michael seems distracted, though. He keeps checking his watch (one of those fancy Apple-watches, Mary Ann notices), and barely makes eye contact with her.

“Let me show you this guy who wants to meet up with me”, Michael says, and shows Mary Ann a photo on his phone of what appears to be a man’s torso – no head. “You can’t see his face?” asks Mary Ann. “Face? Lol.” says Michael, “I can see his 6% bodyfat and I’m interested”. Mary Ann doesn’t know what “bodyfat” is, but doesn’t want to ask since that might make her seem unsophisticated.

After brunch, the two stop at a Cannabis store and buy some chocolate snacks. Mary Ann eats one, and says goodbye to Michael, and goes for a walk to Golden Gate Park. She starts to feel strange: is this what pot makes you feel like, Mary Ann thinks? Time seems – slower, but also faster; the grass seems a bit greener. She falls asleep on the grass, under a Monterey Pine. When Mary Ann wakes up, she is freezing: the fog has come in, blowing away the smoke. She forgot a jacket.

**

A few days later, Mary Ann finds an apartment. Well, not so much an apartment, as a room in an older woman’s apartment. But it is affordable, and she’s told, in a good location. Meanwhile, Mary Ann has found work as a caterer (on the weekends), and a waitress at a Peruvian restaurant downtown. She has not had any replies yet from office jobs.

The woman’s name is Anna Madrigal, and she is kind, if a bit mysterious. She and Mary Ann find themselves sitting in Anna’s living room, which Mary Ann now shares. Anna seems upset.

“What’s wrong?” Mary Ann asks.

“Well -” Anna Madrigal begins, “it’s just that the President – Trump – he’s going after transgender rights again. He is trying to get the Justice Department to basically nullify the definition of transgender as a third sex and thus force us into binary understandings of gender.”

Mary Ann is confused, but listens. Later, she Googles “transgender”.

**

DeDe Halcyon, eldest daughter of business titan Edgar Halcyon, is packing up her last boxes. She and her husband Beauchamp are moving. Having lived in Pacific Heights for decades, they finally decided that she and Beauchamp should make a new start in Nashville, Tennessee (and Beauchamp is from the South, anyway). It will be nice to be closer to family and oh, the things they could do by saving $10,000 a month on rent.

On the way out of the city, crossing the Bay Bridge in their Subaru, DeDe takes a look back at the smoke-filled sky; the new Salesforce Tower standing watch like a sentinel. In Oakland, DeDe notices a tent city under the elevated freeway – she had not seen this before. And further along, a row of what look like tiny dog-houses. She wonders: are people living there, or animals? This is her last thought as the Subaru leaves the urban sprawl and heads East, toward the Sierra Nevada (now engulfed in flames); toward Nevada; toward Nashville.

*

The landmark has graced one of San Francisco’s tallest hills (Telegraph Hill) as a testament to art, architecture and design and is one of the most iconic images associated with the city, towering over the Bay and visible from many points around the Bay Area.

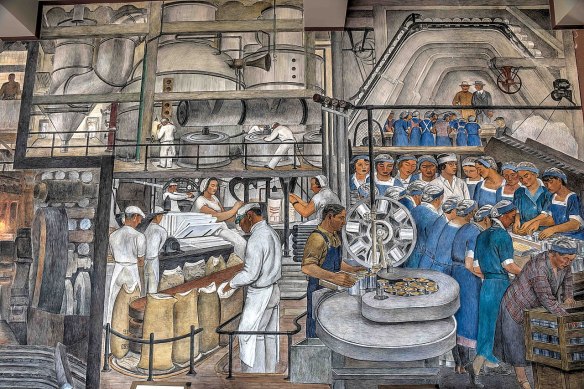

The landmark has graced one of San Francisco’s tallest hills (Telegraph Hill) as a testament to art, architecture and design and is one of the most iconic images associated with the city, towering over the Bay and visible from many points around the Bay Area. (Above – Maxine Albro’s ‘Agriculture of California’)

(Above – Maxine Albro’s ‘Agriculture of California’) A visit to the Coit Tower, therefore, is both an aesthetic and political experience, immersing the visitor into the ‘structure of feeling’ (to borrow from Raymond Williams, 1977) of the mid 1930s against the backdrop of present-day San Francisco. This is a study in contrasts. San Francisco, wealthy then, but now the golden and somewhat dystopian center of the global technology industry, beckons from the tower’s windows. The murals, however, produce an affect of simultaneous darkness and optimism, and one steps into the uncertainty, dread, hope and electric energy of the 1930s when entering the tower’s lobby.

A visit to the Coit Tower, therefore, is both an aesthetic and political experience, immersing the visitor into the ‘structure of feeling’ (to borrow from Raymond Williams, 1977) of the mid 1930s against the backdrop of present-day San Francisco. This is a study in contrasts. San Francisco, wealthy then, but now the golden and somewhat dystopian center of the global technology industry, beckons from the tower’s windows. The murals, however, produce an affect of simultaneous darkness and optimism, and one steps into the uncertainty, dread, hope and electric energy of the 1930s when entering the tower’s lobby.

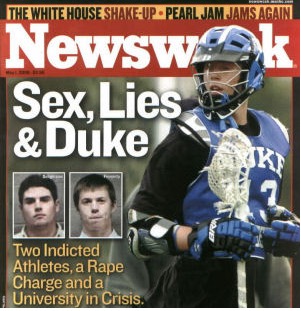

Eventually, it came to light that prosecutor Mike Nifong had withheld evidence that exonerated the three accused (pictured above); and further details emerged that the accuser, Crystal Mangum, had lied about being raped. Mike Nifong was subsequently disbarred; and state attorney general Roy Cooper (now North Carolina’s governor), dropped all charges. Still, the city, and the university, were tainted by the fact that the party did take place; that strippers were hired; that disgusting emails and misogynistic / racial slurs were indeed uttered. The fact remains that an elite university, full of (mostly) affluent students from (mostly) other places, can be an uneasy bedfellow to a Southern industrial city with a high African-American poverty rate and a city where nonwhite residents outnumber white residents.

Eventually, it came to light that prosecutor Mike Nifong had withheld evidence that exonerated the three accused (pictured above); and further details emerged that the accuser, Crystal Mangum, had lied about being raped. Mike Nifong was subsequently disbarred; and state attorney general Roy Cooper (now North Carolina’s governor), dropped all charges. Still, the city, and the university, were tainted by the fact that the party did take place; that strippers were hired; that disgusting emails and misogynistic / racial slurs were indeed uttered. The fact remains that an elite university, full of (mostly) affluent students from (mostly) other places, can be an uneasy bedfellow to a Southern industrial city with a high African-American poverty rate and a city where nonwhite residents outnumber white residents.

In the exercise above, Chung (pictured) asked participants to arrange the chairs (pictured) in ways in which one chair was more powerful than the others. Hinting at Foucault’s (1980) ‘circular’, rather than hierarchical view of how power operates, Chung noted the multiple ways of reading power in any given architecture. If one chair is placed ahead; it has all the power and yet none. If the chair is placed on top of the others, it has power that can be removed if the base becomes precarious.

In the exercise above, Chung (pictured) asked participants to arrange the chairs (pictured) in ways in which one chair was more powerful than the others. Hinting at Foucault’s (1980) ‘circular’, rather than hierarchical view of how power operates, Chung noted the multiple ways of reading power in any given architecture. If one chair is placed ahead; it has all the power and yet none. If the chair is placed on top of the others, it has power that can be removed if the base becomes precarious. In another activity, (pictured above), participants played the roles of student (facing) and teacher (back turned). The student was asking for an extension on an assignment; the teacher was attempting to stand firm on “no”. The difficult negotiation of playing (even non-deliberately) the role of ‘oppressor’, and the many contradictions inherent, made this challenging for both players.

In another activity, (pictured above), participants played the roles of student (facing) and teacher (back turned). The student was asking for an extension on an assignment; the teacher was attempting to stand firm on “no”. The difficult negotiation of playing (even non-deliberately) the role of ‘oppressor’, and the many contradictions inherent, made this challenging for both players. Other activities involved movement only: a participant in the center of a circle, hands outward, led two others, who then led two others, and so on, until the whole room became a swirling mass of human movement which was more chaotic at the circle’s outer edges. This, explained Chung, represents the power dynamic of a society, an institution, a capitalist economy, or a State (a school of fish? A complex adaptive system? a digital network?). The point being that the individual at the center can dictate a mass of related actions / reactions by relatively small movements; those at the outer edges must fight harder to stay with the circle.

Other activities involved movement only: a participant in the center of a circle, hands outward, led two others, who then led two others, and so on, until the whole room became a swirling mass of human movement which was more chaotic at the circle’s outer edges. This, explained Chung, represents the power dynamic of a society, an institution, a capitalist economy, or a State (a school of fish? A complex adaptive system? a digital network?). The point being that the individual at the center can dictate a mass of related actions / reactions by relatively small movements; those at the outer edges must fight harder to stay with the circle.